The Polaris Expedition

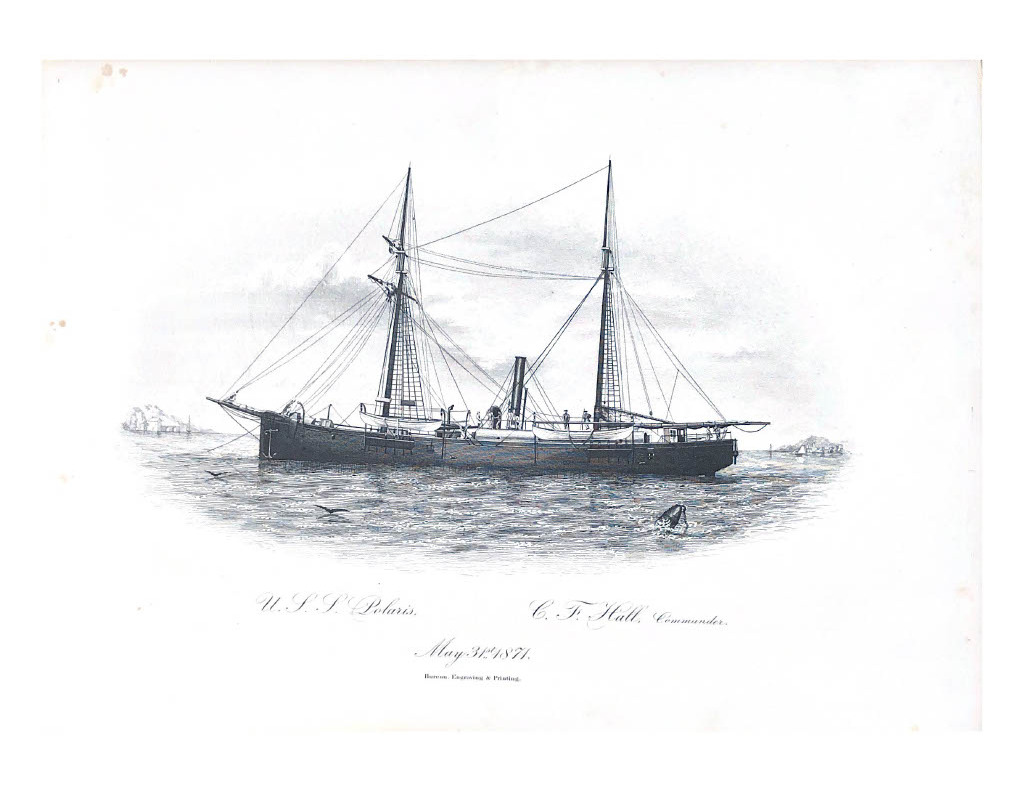

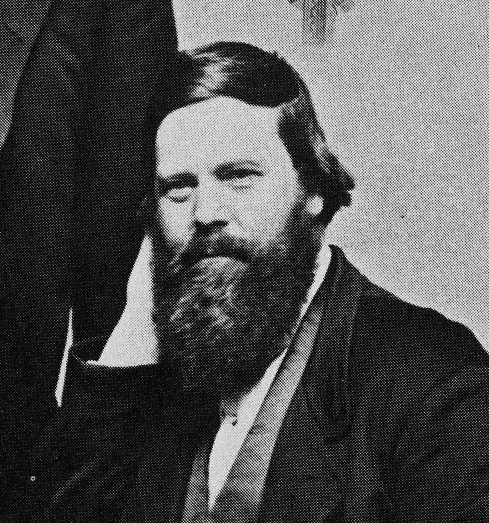

The Polaris was the first major foray by the United States into Arctic exploration. Lead by Captain Charles Francis Hall, the goal of the Polaris expedition was to reach the North Pole, taking scientifiic measurements as they went [1]. The expedition lasted from 1871 to 1873.

Fiskernaes

Captain Hall landed at Fiskernaes, an indigenous settlement, seeking the help of Hans Hendrick as a hunter and dog-driver for the expedition.

Going Down the Road Feeling Bad?

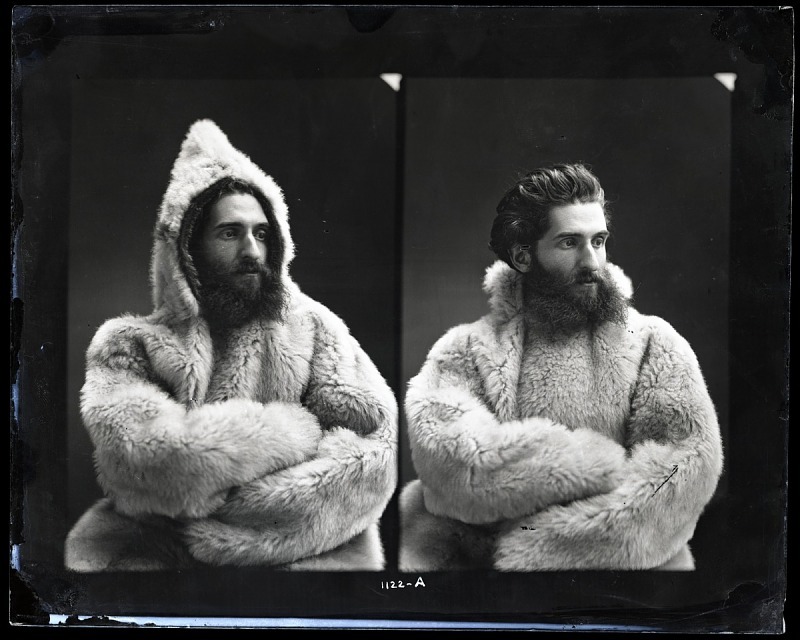

Although self-taught explorer Charles Hall made his lucky break when the U.S. government approved funding for his third expedition, it would be his final adventure. In search of a route through Smith Sound to the North Pole, the fateful Polaris set sail for Baffin Bay in fall 1871 [5]. But Captain Hall faced difficulties from the start, with verbal altercations occuring between Hall and lead scientist Emil Bessels (both pictured). Hall's previous expeditions were smaller-scale journeys with Inuit assistance. The Polaris was a much larger, more complex endeavor. Depsite these struggles, the north-bound ship reached a wintertime landing spot in Northern Greenland in September 1871.

The Death of Captain Hall

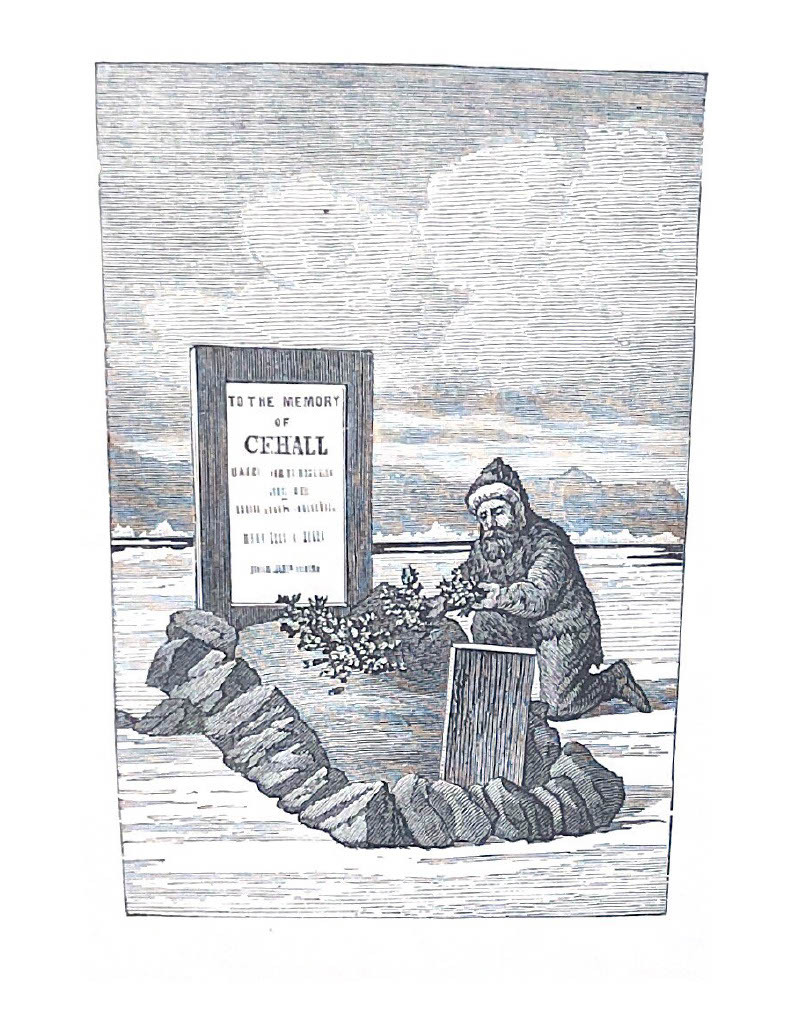

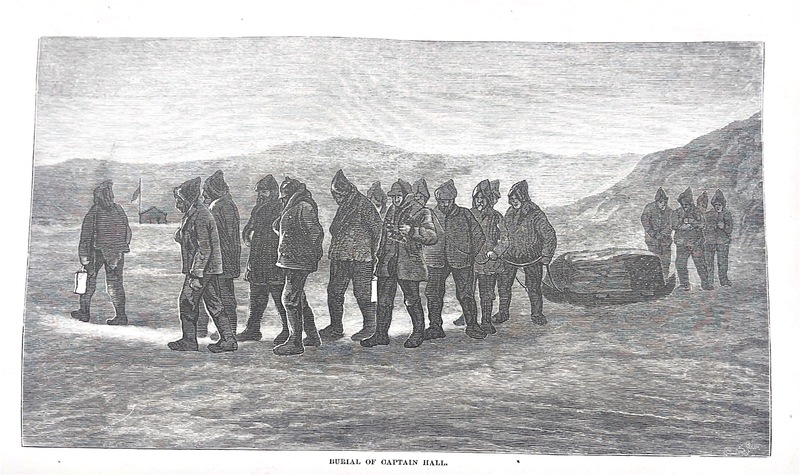

Shortly following a sled journey from the ice-bound Polaris, Captain Hall experienced a turn of health. As he enjoyed a cup of coffee, strong symptoms overcame the intrepid leader. It would only be several days of worsening sickness before his untimely death.

Due the intensity and severity of Captain Hall's condition, speculation of foul play emerged. Of course, mistrust between lead scientsit Emil Bessels and Captain Hall was documented before the illness. Moreover, Bessels and Hall both shared affection for—and had written letters to—a contemporary sculptor Vinnie Ream [3]. As Hall's condition worsened, he refused bedside treatment from Bessels, claiming he was being poisoned. Posthumous examination indicated that arsenic poisoning contributed to his death, but it is unclear if this toxin accumulated naturally, through the explorer's canned food diet, or through direct poisoning from Bessels or another crew member [2].

“Captain Hall is sick; it seems strange, he looked so well… this sickness came on immediately after drinking a cup of coffee” (160)- George Tyson on Captain Hall's declining health in his 1874 book "Arctic Experiences"

Takeaways from Polaris

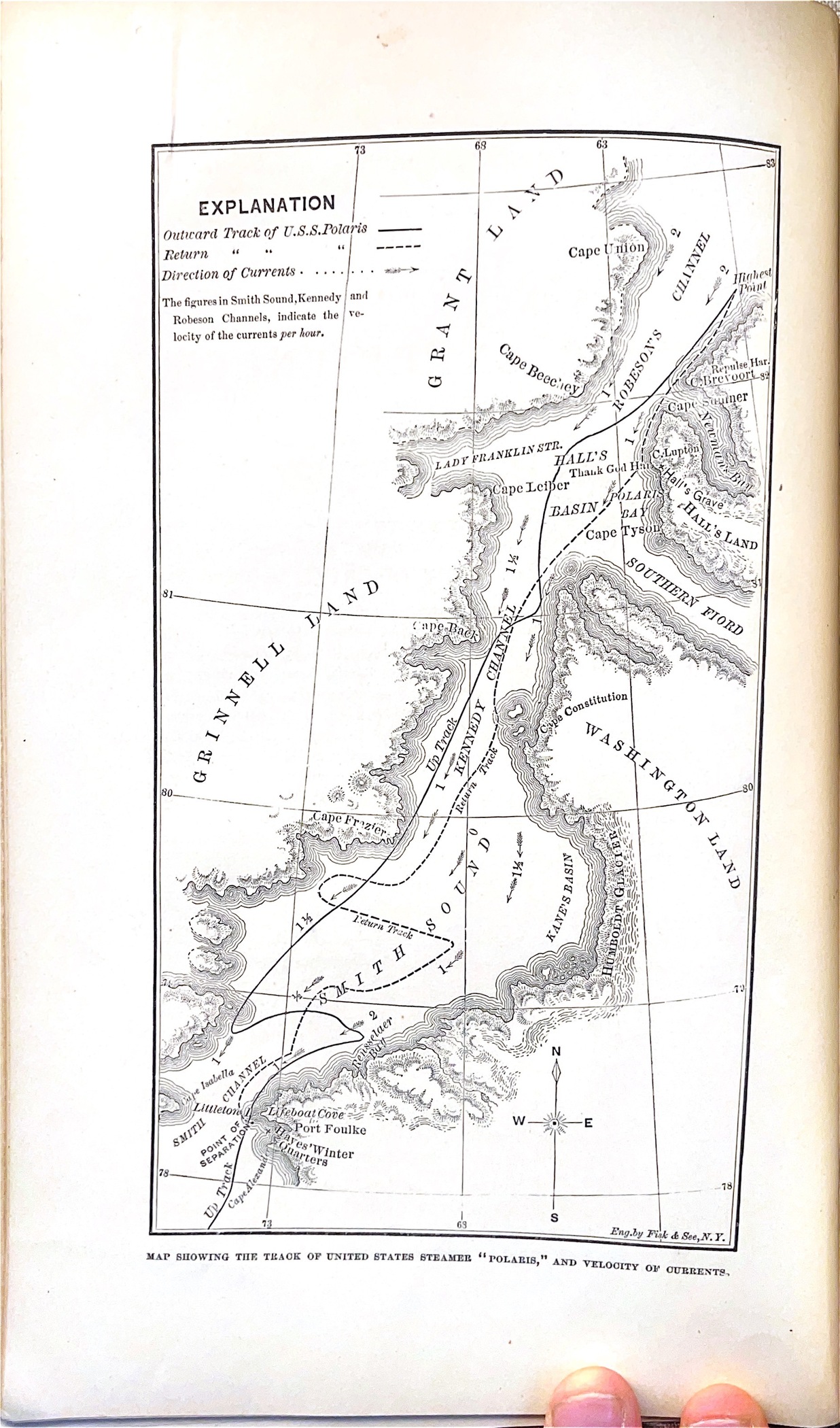

A 1874 Nature article discusses notable takeaways at the time of the expedition's completion: "The results of the expedition may be summed up briefly as follows:—(1) the Polaris reached 82°16'N., a higher latitude than has been attained by any other ship; (2) the navigability of Kennedy Channel has been proved beyond a doubt; (3) upwards of 700 miles of coastline have been discovered and surveyed; (4) the insularity of Greenland has been proved; and (5) numerous observations have been made relating to astronomy, magnetism, force of gravity, ocean physics, metereology, zoology, ethnology, botany, and geology" [1].

Nearly a year after Hall's unfortunate death, the crew faced another tragic event as 19 members found themselves stranded on an ice floe. Days later, the remaining crew grounded the Polaris on the coast of Greenland. After making shelter there and braving the harsh winter, this senior crew was recovered the following June, reuniting with the 19 stranded members who were saved in April 1873. Returning home, this venture—that pushed beyond past journeys despite fateful disaster—was finally concluded.

Sources

[1] “Scientific Results of the ‘Polaris’ Arctic Expedition.” Nature (London) 9, no. 230 (1874): 404–405. https://search.library.dartmouth.edu/permalink/01DCL_INST/134hn0f/cdi_scopus_primary_282481622

[2] Niekrasz, E. (2020, August 13). Wait. Did That Really Happen? Potential Poison on the Polaris. Smithsonian Institution Archives. https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/wait-did-really-happen-potential-poison-polaris

[3] Phillips, B. (2022, November 22). This Arctic murder mystery remains unsolved after 150 years. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2022/11/this-arctic-murder-mystery-remains-unsolved-after-150-years

[4] Smithsonian Digital Volunteers. (n.d.). Charles Francis Hall’s Expedition Diary Volume III, First Expedition August 1860—November 1860. https://transcription.si.edu/project/8115

[5] Wamsley, Douglas W. "Polaris: The Chief Scientist's Recollections of the American North Pole Expedition, 1871-73." Arctic 71, no. 2 (06, 2018): 232-233. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/polaris-chief-scientists-recollections-american/docview/2064961427/se-2